Resources

Patients and Families

Bowel transplantation was first attempted in humans during the 1960s. At that time, patients were dying of starvation after having a large portion of their bowel removed because of disease or trauma. Parenteral (intravenous) feeding was not yet available, and surgeons hoped that the transplanted bowel would function normally. These first intestinal transplant patients died, however, from technical complications, rejection, or infection. Successful intestinal transplants were not performed until the early-1980s. Most grafts during this era were lost to technical problems and rejection. Following the introduction of tacrolimus Prograf® (FK506, tacrolimus) (in 1994 based on the studies done in Pittsburgh, there was a demonstrable drop in rejection leading to improvement in graft and patient survival. For patients transplanted at centres of excellence the actuarial overall patient survival rate now is 93% at 1 year, 70% at 5 years and 50% at 10 years.

As of June 2013, there have been 2584 reported cases of intestinal transplantation in 2398 patients as reported in International Transplant Registry. 70% of patients have been successfully weaned off parenteral nutrition and are on a normal diet, enjoying a healthy lifestyle after intestinal transplantation . Several technological advances have led to modification of operative techniques in the donor and recipient leading to reduction in operating time, better preservation of allograft and implementation of novel techniques. Introduction of newer immunosuppressive strategies have led to significant improvement in 1, 5 and 10 year graft and patient survival rates. Good outcomes have also prompted surgeons to offer re-transplantation in selected cases leading to improved quality of life and prevent patient death.

Outcomes following intestinal transplant than other solid organs. Possible reasons include:

- The intestinal epithelium is more antigeneic and its large absorptive surface expresses donor HLA and non-HLA antigens

- Large number of white cells in the bowel are readily available to mount an immune response

- Large number of bacteria in the gut increases the risk of infection after transplantation

- Patients are ‘high maintenance’ since they require intensive monitoring during the first few weeks following transplantation and close observation while they are at home following discharge

Patients must take anti-rejection drugs to suppress their immune system so their body will accept the transplanted bowel. They must take enough drugs to prevent rejection, but not too much that could lead to infection and sepsis. Prograf® (FK506, tacrolimus) is the most common anti-rejection drug used.

Patients with poor intestinal function who cannot be maintained on intravenous feedings are potential candidates for transplantation. Sometimes, most of the bowel has been surgically removed to treat the intrinsic disease. This produces ‘short-gut syndrome’, which is the most common cause of intestinal failure. Sometimes, the entire intestine is present, but it is unable to absorb enough fluids and nutrients.

Intestinal rehabilitation is the first step to ensure that all possible remedies have been tried. This includes a multidisciplinary approach to patient management involving the expertise of nutritionists, pharmacists, gastroenterologists, pediatricians.

Common indications for intestinal transplantation include:

- Short-gut syndrome caused by volvulus, gastroschisis, trauma, necrotizing enterocolitis, ischemia, Crohn’s disease¸ radiation enteritis

- Poor absorption caused by microvillus inclusion disease, secretory diarrhea, autoimmune enteritis

- Poor motility caused by pseudo-obstruction, aglionosis (Hirschprung’s disease), visceral neuropathy

- Tumor such as desmoid tumor, familial polyposis (Gardner’s disease)

Most children and adults do well on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and transplantation may not be indicated for these patients. In some of these patients appropriate managements and intestinal salvage operations like exploration and adhesionolysis and STEP procedures can restore intestinal integrity and lead to good absorption. Transplantation, however, is a potentially life-saving option for patients with intestinal failure in whom salvage surgery has failed or who cannot tolerate TPN. Because patients’ survival rates are better after isolated bowel transplants, this is the preferred type of transplant. Combined intestinal-liver transplants or cluster transplants are options for patients who developed liver failure on TPN or for patients who have large, local tumors that can only be removed by removing several organs.

The intestine has been more difficult to transplant than other solid organs. Possible reasons include:

- the large number of white cells in the bowel provides a strong stimulus for rejection and

- the large number of bacteria in the gut increases the risk of infection after transplantation.

Patients must take anti-rejection drugs to suppress their immune system so their body will accept the transplanted bowel. They must take enough drugs to prevent rejection, but not too many or they may have problems with infection. Prograf® (FK506, tacrolimus) is the most common anti-rejection drug used.

Patients with poor intestinal function who cannot be maintained on intravenous feedings are potential candidates for transplantation. Sometimes, most of the bowel has been surgically removed to treat the disease. This produces the short-gut syndrome, which is the most common cause of intestinal failure. Sometimes, the entire intestine is present, but it is unable to absorb enough fluids and nutrients.

Diseases leading to intestinal transplantation include:

- short-gut syndrome caused by volvulus, gastroschisis, trauma, necrotizing enterocolitis, ischemia, Crohn’s disease

- poor absorption caused by microvillus inclusion, secretory diarrhea, autoimmune enteritis

- poor motility caused by pseudo-obstruction, ananglionosis (Hirschprung’s disease), visceral neuropathy

- tumor or cancer such as desmoid tumor, familial polyposis (Gardner’s disease)

Most children and adults do well on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and transplantation may not be indicated for these patients. Transplantation, however, is a potentially life-saving option for patients with intestinal failure who cannot tolerate TPN. Because patients’ survival rates are better after isolated bowel transplants, this is the preferred type of transplant. Combined intestinal-liver transplants or cluster transplants are options for patients who developed liver failure on TPN or for patients who have large, local tumors that can only be removed by removing several organs.

Most intestinal grafts come from deceased donors— people who have been declared brain dead in a hospital while attached to a ventilator (artificial breathing machine). Consent is given by the next of kin for organ removal and transplant. Occasionally, a portion of the bowel is taken from a living donor— a relative such as a parent or sibling for live donor intestinal transplantation.

Improved anti-rejection drugs, refined surgical procedures, and a greater understanding of immunology have contributed to successful intestinal transplants. Short-term survival is now comparable to lung transplantation results. International Intestinal Transplant Registry is a comprehensive database of patients who have received intestinal transplantation.

Prograf® (tacrolimus) has been given to most intestinal transplant patients over the past 20 years. The commonest cause of death following intestinal transplantation is from sepsis, multiple organ system failure or rejection. Some patients have died of post transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Intestinal transplantation has become the standard of care for intestinal failure in patients in whom intestinal rehabilitation has been unsuccessful or is not possible. It has evolved over time resulting in short-term graft survival rates that are similar to the results of other solid organ transplants. Clinicians and scientists are working on strategies to ensure long term graft and patient survival.

Newer methods to diagnose rejections are being introduced in addition to immunologic monitoring utilizing measurement of donor specific antibody titers, anticipating rejection episodes and treating them before a full blown clinical rejection develops. Introduction of better infectious prophylaxis has reduced the incidence of infections as deaths as well.

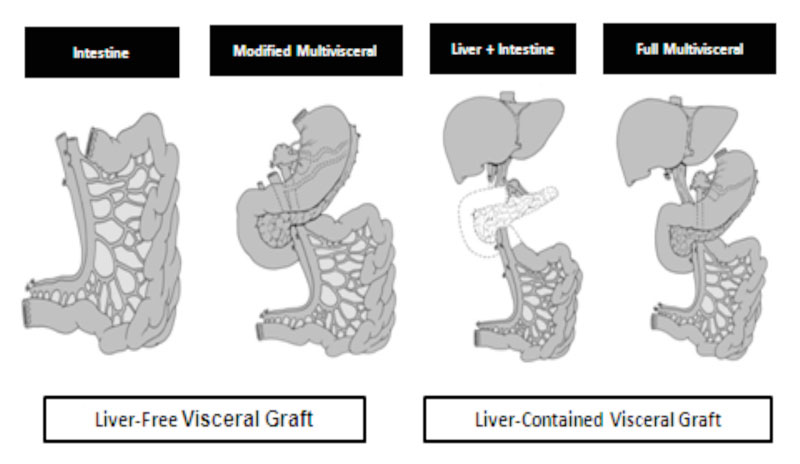

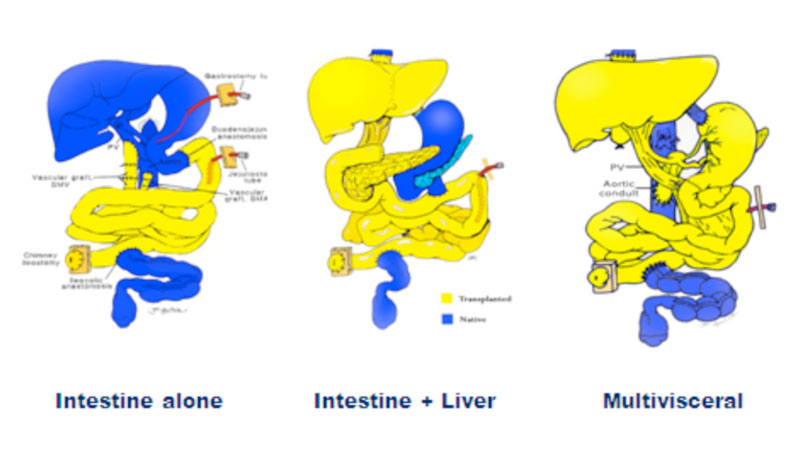

There are four main types of intestinal transplantation:

- Isolated intestinal transplantation

- Liver intestine transplantation

- Multivisceral transplantation

- Modified multivisceral transplantation

Types of visceral allografts; intestine, liver-intestine, and multi visceral. Inclusion of the pancreaticoduodenal complex (unshaded organs) is optional with the liver-intestine allograft. A multivisceral graft must include the stomach en bloc with the other visceral organs without (modified) or with (full) the liver. The colon, pancreas and kidney could also be added en bloc to the visceral allograft with the exception of the liver-free visceral allograft when the kidney can only be transplanted separately.

Types of visceral allografts; intestine, liver-intestine, and multi visceral. Inclusion of the pancreaticoduodenal complex (unshaded organs) is optional with the liver-intestine allograft. A multivisceral graft must include the stomach en bloc with the other visceral organs without (modified) or with (full) the liver. The colon, pancreas and kidney could also be added en bloc to the visceral allograft with the exception of the liver-free visceral allograft when the kidney can only be transplanted separately.

Reproduced (with permission) from Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery

J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 Nov;14(11):1709-21. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1317-5. Epub 2010 Sep 17.

Intestinal transplantation is a complex procedure that can lead to several technical and non-technical complications. Technical complications include anastomotic leaks and vascular thrombosis, Postoperative sepsis can be avoided by appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis. Because of the high doses of immunosuppressive medications, intestinal transplant recipients are at higher risk of infection compared to other transplant recipients.

Intestinal rejection can be acute cellular, occurring within 90 days following transplantation or acute humoral or antibody mediated rejection. These are treated with steroids, tacrolimus or antilymphocyte antibody induction.

Chronic rejection occurs over a period of time and is diagnosed when there is chronic intestinal failure and biopsy confirms loss of villia and onset of fibrosis and vasculopathy. Some of these patients may require allograft enterectomy and retransplantation.

Post transplant lymphoproliferative disorder is a consequence of immunosuppressive therapy. In general it is EBV related and can be treated promptly if diagnosed early.

Graft Versus Host Disease is not uncommon in intestinal transplant patients since intestines carry a large lymphatic system overload. Appropriate management includes optimization of immunosuppressive therapy.

Some centers have following a stepwise immunosuppression weaning policy following intestinal transplantation. In Pittsburgh series, 50% of patients were weaned to single dose schedule of tacrolimus twice a week. Attempts are being made to institute protocolized, biopsy guided weaning in patients in some centres.

Information for Clinicians

Selected References

-

Abu-Elmagd KM. The small bowel contained allografts: existing and proposed nomenclature. Am J Transplant 2011;11:184-5.

-

Oliveira C, de Silva N, Wales PW. Five-year outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:931-7.

-

Ngo KD, Farmer DG, McDiarmid SV, et al. Pediatric health-related quality of life after intestinal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant 2011;15:849-54.

-

Pironi L, Staun M, Van Gossum A. Intestinal transplantation. The New England journal of medicine 2009;361:2388-9; author reply 9.

-

Sudan D. Long-term outcomes and quality of life after intestine transplantation. Current opinion in organ transplantation 2010;15:357-60.

-

Farmer DG, Venick RS, Busuttil RW. Improving outcomes after intestinal transplantation at the University of California, Los Angeles. Clin Transpl 2010:245-52.

-

Mazariegos GV, Steffick DE, Horslen S, et al. Intestine transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1020-34.

Intestinal Transplant Registry

Intestinal Registry’s Scope

Mission

The mission of the ITR is to provide data on the outcomes of intestine transplantation to the international intestine transplant community in order to support their efforts and improve outcomes as well as inform policy development.

Background

The Intestinal Transplant Registry (ITR) is currently managed by the Intestinal Transplant Association (ITA) under the direction of Matthew Everly. Analyses are directed by the Research Committee of the Association.

The Registry has collected data on the world-wide outcomes of intestine transplantation since 1985. Data are provided every two years by participating centres. It is compiled, verified, analyzed, and presented in aggregate form only at the Bi-Annual meeting of the ITA. Specific queries about outcomes are provided to participating centres upon request.

Data Collected

Currently, the Registry collects the following information:

- Donor information

- Recipient demographics, such as gender and age

- Pre-transplant diagnosis leading to transplant

- Pre-transplant status (the patient’s condition before transplant)

- Type of transplant (bowel; bowel & liver; or “cluster transplant”)

- Post-transplant status and complications

- Anti-rejection drugs taken by patients

Analyses

- Descriptive reports of donor and recipient profiles; and transplant outcomes

- Inferential Analyses to determine factors affecting outcomes by means of:

- Pre-transplant diagnosis leading to transplant

- Pre-transplant status (the patient’s condition before transplant)

- Univariate analyses (data checking and validation)

- predictive multinomial model building

Privacy and Confidentiality

Data are presented in aggregate form only, and international privacy and data security have been met ensure patient data and centre confidentiality.

To visit the Intestinal Transplant Registry website, please visit www.intestinaltransplant.org

It is highly advisable that the update be done electronically, through the Microsoft Access file sent to each centre. If this is not possible, we have set up an online form on this site that allows paper based centres to update without the need to physically mail the forms or fax them.

Please fill out the online form for each patient, AND attach the corresponding PDF* form for each patient for verification purposes.

- For patients Transplanted after May 31, 2007 - New Patient Forms (BETA)

- For patients Transplanted before May 31, 2007 - Patient Update Form (BETA)

In case of any doubts or inquiries regarding ITR patient forms please contact:

Max Marquez, MD

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Our Commitment to Privacy and Security

Data Use Policy

The Intestinal Transplant Association (herein “recipient”) collects and utilizes a limited patient data set from its participating centres (herein “sender”) as described in the Statement of Agreement.

Privacy Agreement

- The sender agrees to be in compliance of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPPA) or other relevant national legal standards including but not limited to adequate institutional approval from the sender.

- The recipient agrees that it shall not use or disclose Personal Health Information (PHI) or Limited Data Set (LDS) information except as permitted under this Statement of Agreement.

- The recipient may use the LDS information received or created by it (a) to perform its obligation under this Agreement consistent with research connected with statistical determination of aggregate outcomes after Intestinal Transplantation as is the mission of the Recipient, and/or (b) to carry our its legal responsibilities if the disclosure is required by law, and/or (c) for data aggregation functions, as defined by HIPPA.

- The recipient is sole entity that is permitted to use or receive the LDS.

- The recipient provides assurance that:

- It shall not use or disclose PHI or LDS information except as permitted under this agreement.

- Appropriate procedural, physical, and electronic safeguards, sufficient to comply and exceed with the requirements of HIPPA, are currently in use in order to prevent any use or disclosure of LDS information other than as permitted or required by this agreement. See Annex A.

- Any information regarding unapproved use or disclosure of PHI or LDS that is neither permitted by this Agreement nor HIPPA shall immediately be reported to Covered Entity.

- PHI and LDS for all subjects will be held confidentially and used or further disclosed only as required by law or for the purpose for which it is disclosed.

- The recipient will use statistical methods to effectively de-identify individual subjects and participating centers. The statistical analyses will examine data in the aggregate form only. There is no conceivable risk that the information will allow identification of a specific study subject or centre.

Annex A

IRTA undertakes reasonable efforts to ensure that all personally identifiable information collected on our site remains secure. The database is within a Secure Server in a Private Network, under strict electronic security measures including: (a) mirrored drives; (b) daily backups; (c) firewall; (d) record level data made anonymous; (e) entire database encryption; (f) password protected server, directory and database file; (g) limited aggregated data set used for analysis in standalone computer. Physical security measures include, but are not limited to: (a) restricted access area with individually logged key entry; (b) locked file cabinets for physical records (if any).

Questions

Questions about the IRTA privacy policy should be addressed to the IRTA web site through the following link .